Project leaders Smith and Legg share insiders perspective on Camden Burials

Dr. Steven Smith, a research professor at the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA) and James Legg, public archaeologist at SCIAA have worked together on and off for several decades on archaeological digs, specifically at military sites. Now they are working together again on another project, this time one that has required their full attention and efforts for the sake of doing what has needed to be done for over two centuries.

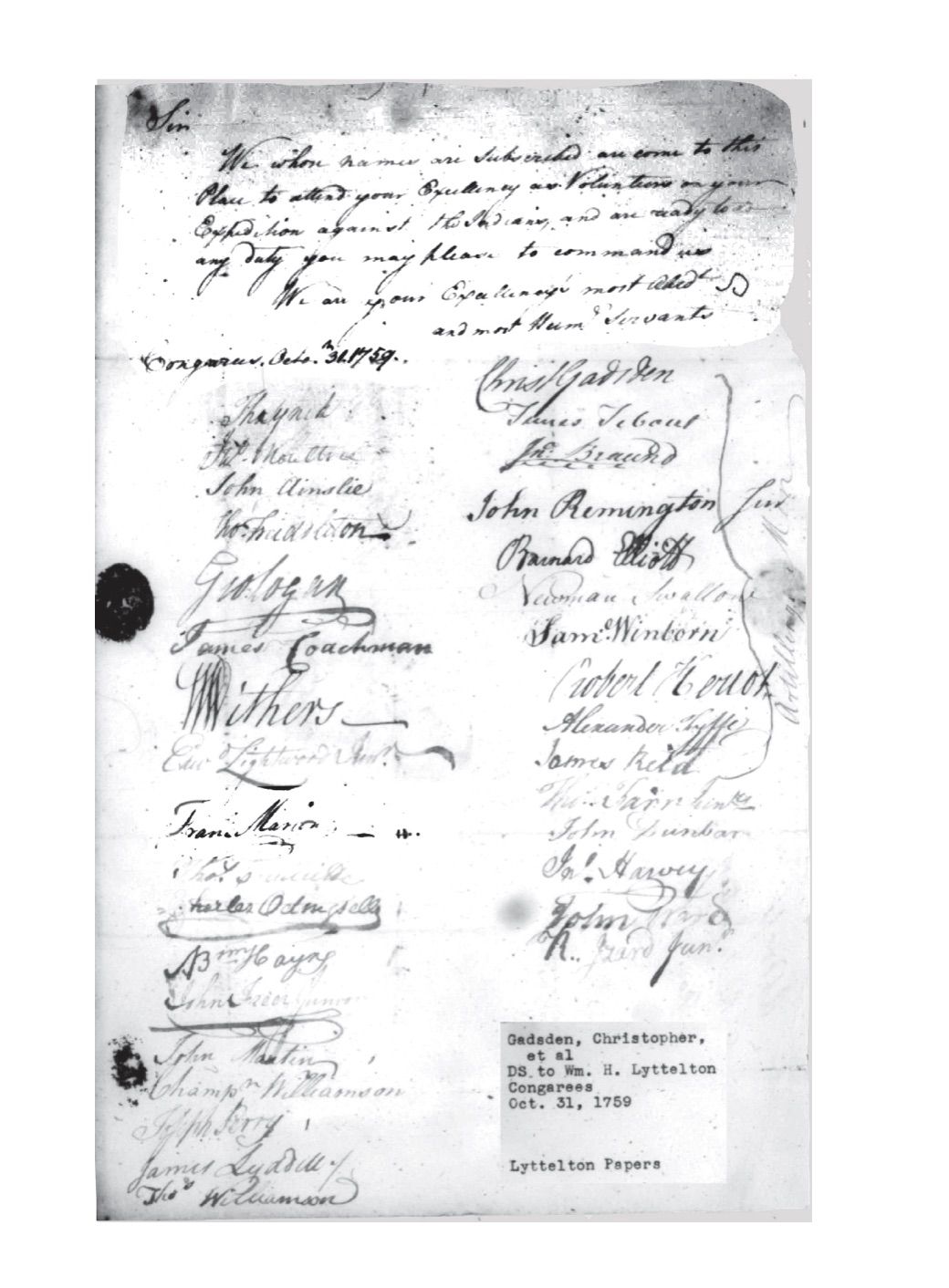

Contracted by Doug Bostick, CEO of South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust, Dr. Smith is the principal investigator on the Camden Burials project with Legg serving as field director. Both familiar with the site prior to the start of the project, Dr. Smith and Legg have worked together conducting field archaeology at the Camden Battlefield site since the early 2000’s. Over the past twenty years they have written two reports on the area, with this project culminating into a third report.

Legg has envisioned this specific project since the early 1980’s when he first became aware of the site and realized there may be burials inches below the surface. He felt that it was important to recover these soldiers’ remains, so that they may be recognized for their sacrifice, and properly honored and reinterned.

However, how well the remains were preserved was uncertain up until three years ago. While the university was closed due to the pandemic Legg found himself coming out to the battlefield almost daily with Dr. Smith accompanying him weekly. In April of 2020 while scouring the field with his metal detector, Legg finally found the reading that confirmed his suspicions from all those years ago.

“That reading was a couple of USA buttons initially, one button that still had enough metal in it to get me a reading.” Legg recollects, “And after I excavated the button, I looked at the hole and I could see that it was deeper than the plow zone. I scraped the bottom of the hole, and sure enough, there was a femur running across the hole.”

From this discovery, Legg has not only witnessed this project come to fruition but also has been an integral part of it while working alongside his longtime colleague Dr. Smith. The project has grown exponentially larger than either of them had anticipated.

“As it developed, the project which was envisioned as a small endeavor by the institute, ended up growing tremendously.” Legg explains, “We ended up with easily four times the number of individuals involved that we had envisioned. Our four-week schedule went to a total of eight-weeks. And our five or six individuals that we had planned to excavate ended up being fourteen individuals in seven different graves.”

Legg initially expected to help with the majority of the excavations but found himself busy instead coordinating the roles of the teams working on the project from the Richland County Coroner’s Office and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.

Dr. Smith reflected that this is the largest project he and Legg have worked on, and his first-time uncovering remains. While the primary goal has been to recover the individuals and rebury them deeply and honorably, the information they are uncovering about the lives of these Revolutionary soldiers has been unparalleled for Dr. Smith.

He explains that they have determined some of the soldiers were only teenagers. They have also been able to learn about health conditions the soldiers may have had, how they died in combat, as well as the location of where they fell during the battle. It’s given further insight into where the units were on the battlefield and how the battle most likely unfolded. This information has also further humanized these remains, bringing it into the foreground that these were actual people, kids even, fighting not for their lives, but for the country they wholeheartedly believed in.

Legg reflects on the most memorable and moving part of this experience being the small, but solemn ceremony given to each soldier after they were removed from the ground. Once laid in the box for transport, a flag was draped over the remains, and escorted by a veteran to the vehicle for transport. He states that while it was a small gesture, it was moving for all who witnessed it.

This project has deeply touched the hearts of the field archeologists, providing moments of honor and reflection. The recovered soldiers and information gleaned from them is something that both men believe will have a lasting impact on historical records from the American Revolution and the public’s understanding of these first veterans of our country.

“This battle has been overshadowed despite it being one of the largest American Revolution battles in South Carolina. It’s important for people to recognize the sacrifice these soldiers made on both sides and to learn about the past.” Dr. Smith shares, “And it brings a reality to what we’re studying. It’s not as abstract as the past being somewhere back there. Someone famously said, ‘Now this is our country and it’s here and it’s real and it happened.’”