Remembering the Many

A salute to the troops of America’s first decisive victory against land and sea forces

from Rick Wise, Interim Executive Director / CEO, Military Historian

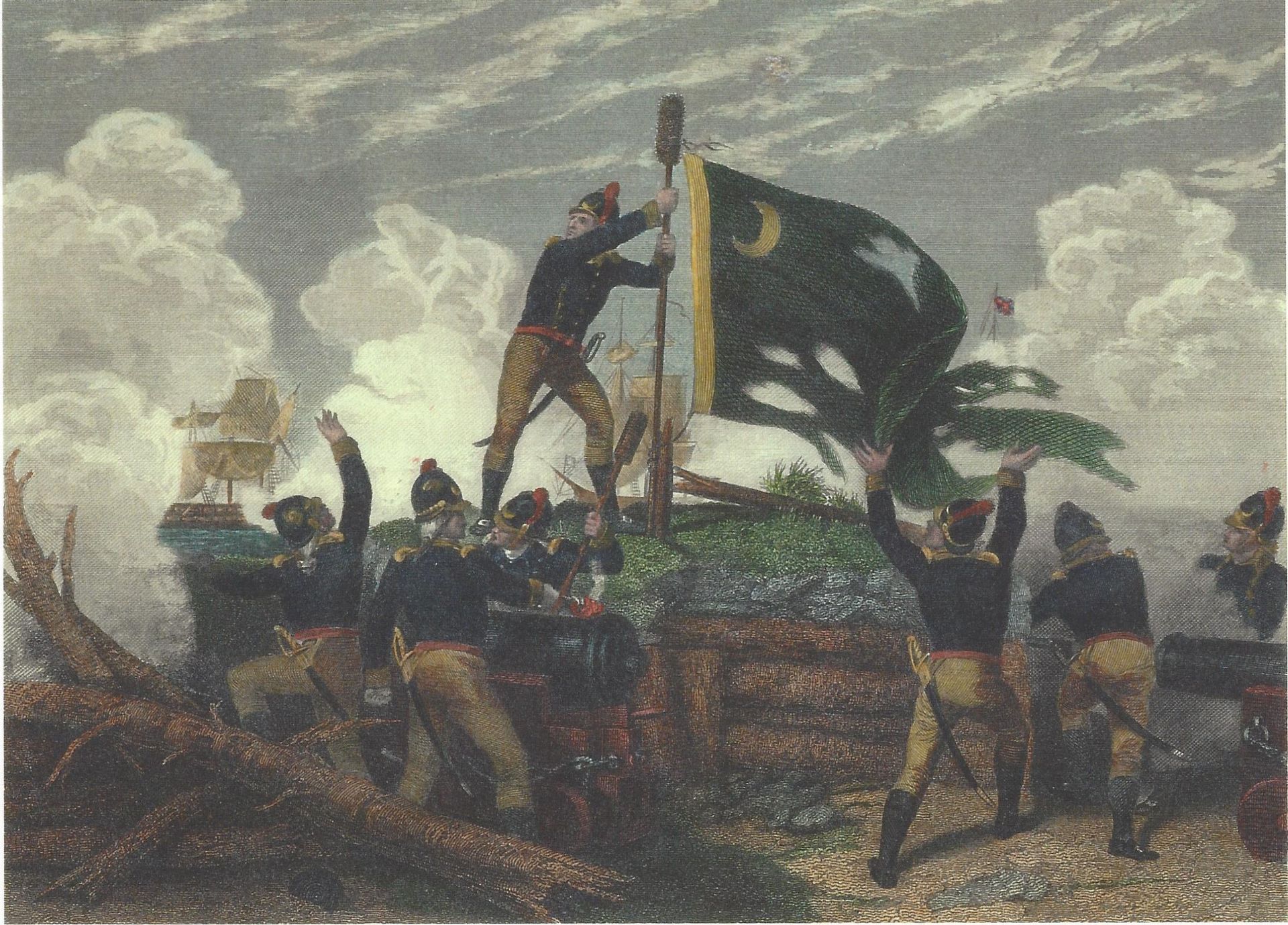

By 9:00 PM on 28 June 1776, it was over. The rotten egg smell of gunpowder wafted across the water of Charles Town harbor, and permeated Fort Sullivan and the surrounding marshes. Colonel William “Danger” Thomson’s troops and the waters of Breech Inlet had held off any attempt by the British infantry to cross from Long Island (Isle of Palms). In the summer twilight, looking across the harbor, it finally became clear to those anxiously waiting in Charles Town that the little palmetto log fort had held. The spongy logs and sand miraculously deflected and absorbed the shot and shell directed at them by the British fleet.

Those mighty ships now limped back to the anchorage at Five-Fathom Hole with splintered rails, decks, and masts. Rigging hung in strips of canvas, frayed ropes, and dangling spars. The dead and wounded sailors were evidence of the accuracy of the cannon fire from the fort. With resounding huzzahs, the soldiers in the fort announced their glorious victory. As their voices echoed across the water, their celebration also marked the first significant victory for the fledgling United States of America in its war with Britain.

Today we revel in the glory of that first, critical victory of the War for Independence. But to accomplish that feat against the strongest country in the world at that time says something about the men who made it happen. Soldiers and sailors, artillerymen, and infantry acting as artillerymen, did their duty and achieved victory that day. But really the full story is overlooked. The combined efforts that made that day possible are all melded into the events of a just few hours of battle. Though we focus our vision on the battles and engagements that happen, it's every day soldiering that win them.

To understand the scope of Carolina Day, is to understand the months’ worth of work by the men, free and enslaved, that made the triumph happen. Starting in January 1776 when the decision was made to make Sullivan’s Island a point of Charles Town’s defense, the task to fortify it began. Troops and enslaved workers were sent to Sullivan’s Island. There was a morass vicinity where the fort was being built with hard labor, with none of the amenities of Charles Town that tempted them across the water. Their days were made of work details to build the fort that Captain Peter Horry described as 500 feet long and 16 feet wide, with sand packed in between. There were countless hours of rafting palmetto logs to the site, the laborious efforts to put them in place, chink the gaps between the logs with sand, build gun platforms, and then mount the heavy guns. Sweat. Heat. Mosquitoes. Fatigue. Humidity. Discipline. Grog. Complaining. All of these, the drudgery that soldiers have endured since the beginning of time.

From March til June those tasks at the fort were mostly same, day in and day out. Sullivan’s Island was no garden spot. Major Francis Marion ordered that the oak trees not be cut, so that the men could have some shade. Building and defending the palmetto log fort with the blue flag with a crescent in the corner flying from its incomplete ramparts, were soldiers of the Second South Carolina Regiment, supported by some men of the Fourth Regiment (Artillery), enslaved workers, and the guidance of officers and engineers. Tedious work, interlaced with drills for quick defense. Another work detail, then training from the artillerymen of the Fourth Regiment on how to work the guns. Training infantrymen to be gunners. Drill on how to repel an enemy landing. Another work detail.

On the north end of the island, Colonel “Danger” Thomson’s men of the Third Regiment did the same, as did the others around the harbor. The British arrived on 2 June, and the work was more strident. Inspections were not promising. The fort not ready, “a slaughter pen,” according to General Charles Lee. But Colonel William Moultrie promised a stout defense by his soldiers. Lee was about to relieve Moultrie and put a more energetic commander in place, but that same morning the British ships sailed into position, and the fight was on. And those haggard soldiers in the little palmetto log fort prevailed.

We all know of the men whose names became famous for their exploits that day, and for their other actions during the war. Names like Moultrie, Marion, Horry, and Jasper. They were with the 435 men who defended that small fortification that most experts expected to be shot to pieces by the British broadsides. We remember those few. I encourage you to remember the many. They are those who remain anonymous in history, except for their appearance on rosters 248 years later. It was their soldiering in desperate times, it was they who endured the hardships necessary when their country in its infancy needed them most. They are the ones who won the battle with duty and sweat, defended the shores at Breech Inlet, and made the indefensible fort hold out against the strongest navy in the world. Their spirits are still with us on Carolina Day. And their spirits are still with those in uniform who anonymously defend our great nation today.