British Embassy Attendance and Involvement at the Camden Burial Funeral and Burial

In a remarkable effort to ensure each soldier receives the highest of military honors and support, there will be a British presence during the funeral procession and burial ceremony.

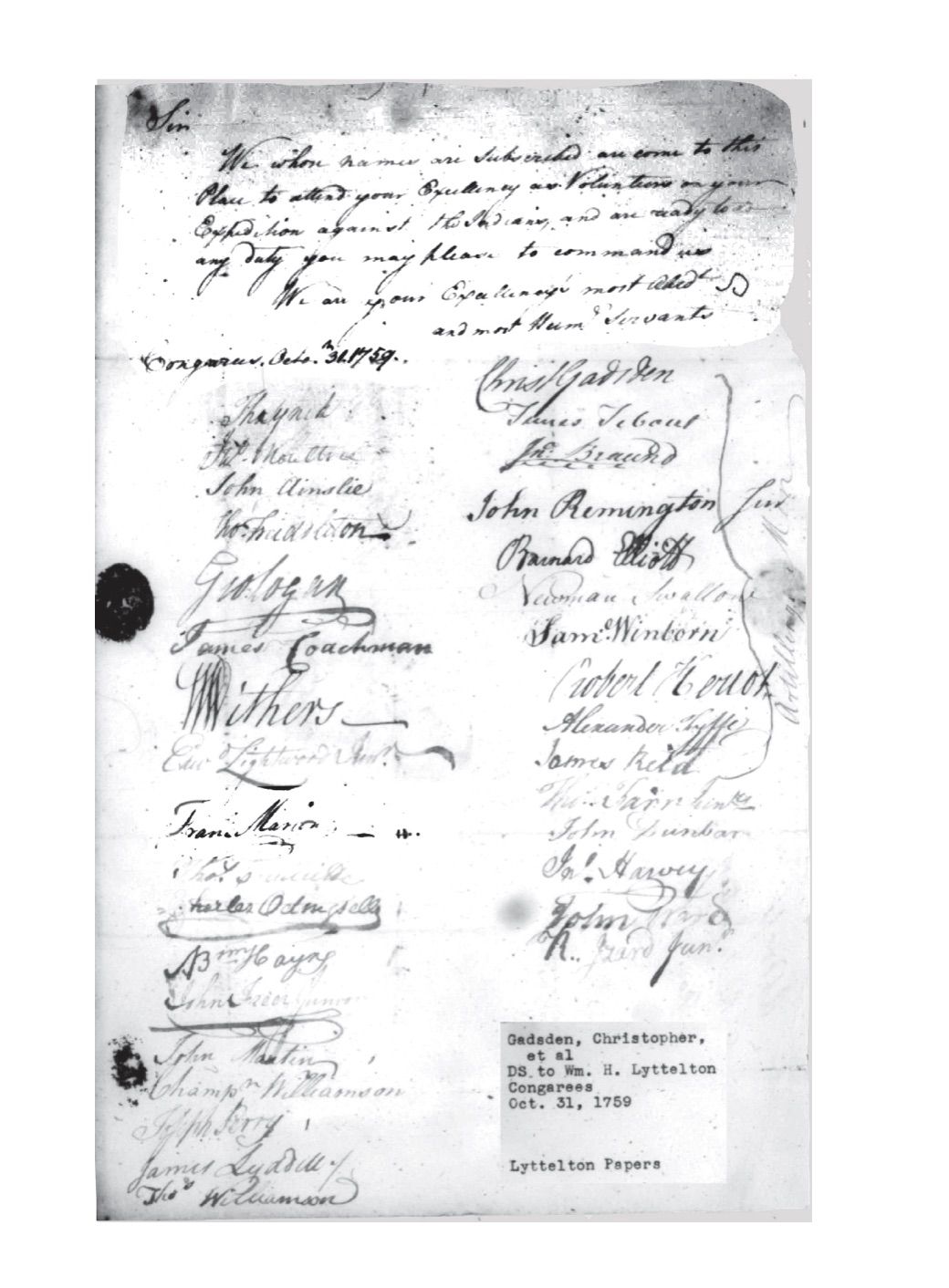

Of the fourteen soldiers’ remains recovered at the Camden Battlefield site, there were twelve patriots, one Loyalist, and one soldier with the British 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser’s Highlanders. In a remarkable effort to ensure each soldier receives the highest of military honors and support, there will be a British presence during the funeral procession and burial ceremony.

Claire Bates, Chief of UK Defense Communications for the British Embassy in the United States, first heard about the Camden Burials project from her colleague who was speaking with contacts in South Carolina. Bates recalls her colleague approaching her with the story, being fascinated and convinced it was something the embassy should support. Bates could not agree more.

While burying Revolutionary War soldiers is certainly a first, Bates shares that being active in the States is not unusual for them, “We attend lots of military exercises and ceremonial events. Wherever we can we turn up in uniform and support our American colleagues we do because it is very important for us to be seen doing what we do together. The UK is the number one ally of the US. I don’t think anyone would argue with that.” Bates continues, “We are always happy to support anything that represents our relationship to its finest. This is a really perfect way of illustrating that.”

Bates further explained that having a British presence at the Camden Burials is symbolic of the transformation of the UK and US relationship since the 18th century. The two countries have migrated from enemies to the closest friends, a change that should be recognized and celebrated. Bates shares that while the relationship between the US and UK is important and should be supported, when possible, the attendance of British soldiers at the events comes from a deeper motivation.

“More importantly than the relationship, it is a soldier who deserves the respect and dignity of a proper burial and that doesn’t matter really if they’re French, German, American, or British. It just so happens that this person is British, and we are there to support,” Bates explains. “Rather it is about giving respect and dignity to someone who fought passionately for a cause they believed in. It’s not really about whose side they were on. It’s just about doing the right thing.”

Furthermore, one of the military attaches at the embassy, Colonel Alcuin Johnson, has direct links to the regiment that the recovered Highland soldier belonged to, and feels passionately that he should be in attendance.

“Remembering our fallen is a fundamental part of life in the military, regardless of when the conflict may have taken place,” Colonel Alcuin shares, “I feel humbled to be able to represent both the British Defense Staff in the United States and the British Army at this important ceremony. It is an honor and a privilege.”

In addition to Colonel Alcuin, the embassy is also sending British soldiers to be pall bearers for the Highlander being buried. A detail from the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Regiment of Scotland will be part of the official ceremonies. There is no shortage of military members interested in being a part of such an importantly historical event.