Historic Caissons Carry Soldiers home

These patriots will move heaven and earth to bury these guys.

The week leading up to the events for the Camden Burials, volunteers from Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, and even as far as Ohio, will be traveling to the town of Camden to lend their time, experience, and resources to properly honor and lay to rest the fourteen soldiers’ remains. While it is an effort that does not go unnoticed, these volunteers are not doing it for the glory, they are doing it for the original veterans of this country and because they believe it is the right thing to do.

Steve Riggs, a seventy-one-year-old veteran himself, is overseeing the coordination of the funeral cortege and the horse-drawn caissons carrying the fourteen soldiers’ remains to the funeral service. Rigg’s recalls when he was contacted about assisting with the funeral procession that there was not one moment of hesitation.

“It’s something that must be done. I have made this commitment. This is not a reenactment; these are fourteen real men. We are burying twelve American soldiers, two British who have been missing in action for 233 years. We are bringing them home.” Riggs continues solemnly, “And I don’t want them to be lost for another two hundred years. We are burying war dead. These are guys who died to give us our freedom. I served to keep our freedom. These guys gave it to us.”

Riggs has been volunteering his time and resources for the past thirty years performing funeral processions with horse drawn caissons- something that exists in roughly five places around the country. Riggs has helped bury the crews from the Hunley, General Pulaski in Savannah, Strom Thurmond, and Captain Kimberly Hampton (the first female pilot in the United States military to be killed in action) to name a few of the many ceremonies he has contributed towards.

However, in all the years of experience this is a first for Riggs finding himself with the honor to organize a military funeral cortege for the first veterans of our country. He has called upon people from all over, past buddies of his he has met over the course of years doing war re-enactments and through his contacts volunteering with the South Carolina National Guard to conduct funerals for those in the military and public service.

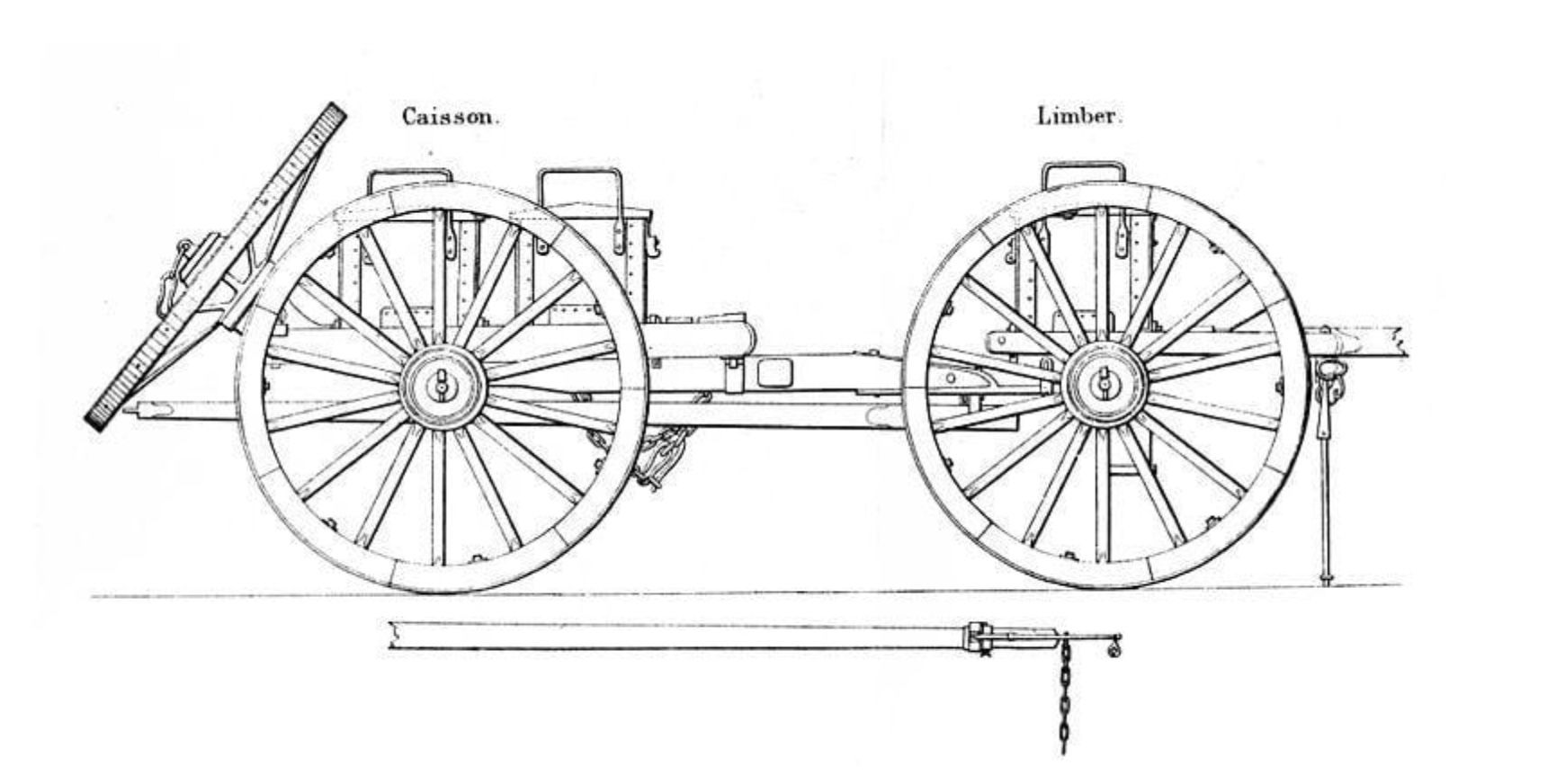

One of these friends is Paul Rice, a Civil War re-enactor, Rice is coming down from Roanoke, Virginia with a group of about fifteen volunteers, two limbers, two caissons, six harnesses, and at least eight horses. Rice’s contribution is one of a few others that will make the military caisson funeral procession possible.

There will be four groups total in the procession, three pulling the twelve American soldiers and one pulling the two British soldiers. Those pulling the American soldiers will don 1924 US army mounted artillery uniforms and those pulling the British will wear World War I British uniforms. There are six horses to a group, each row has one rider and one riderless horse. The horses pull a limber behind them which in turn pulls the caisson that the soldiers’ coffins will lay atop. In the case of the two British, they will be carried atop a gun carriage.

Riggs explained that the British do not use caissons in their military funerals and that the tradition began by soldiers placing their wounded on the caissons during battle for transport off the field. In each group there will be a seventh horse untethered with a rider that leads the group, known as the chief of caisson or chief of peace, respective to the caisson or gun carriage.

While Riggs and Rice both have experience using a caisson in re-enactments, Riggs hopes that everyone present for the funeral procession does not forget that these are soldiers who were once alive and breathing and now are being laid to rest. He also recognizes the feat of pulling off a funeral cortege with horse-drawn caissons of this magnitude is not something he could do alone.

“I am heading up the program, but I can’t do it, really, without all my friends. They’re the heroes. They’re the guys who are coming to help me do this because it means something to them,” Riggs shares, “To me that’s the story: across America the word went out that we had fourteen Revolutionary soldiers who died for their country that need to be reburied. Who will come help us? And these guys all raised their hands. These patriots will move heaven and earth to bury these guys. That to me is the miracle.”

Over two hundred and thirty years later veterans and patriots alike are coming together to bring these men home, so that they may finally find a place for their souls to rest.