Camden Coffin Craftsmen

No stone has been left unturned throughout the process of excavating, analyzing, and planning for the ceremony set to honor these soldiers in April–including their coffins. Meet the men behind the coffins.

The sound of the saw cutting through wood with the smell of sawdust clinging to the air, while not too far away the steady pound of a hammer against metal reverberates off the walls of the workshop. These sounds and smells surpass time spanning over centuries of woodworkers and blacksmiths, building and forging creations for both the living and the parted.

The remains of the fourteen soldiers archaeologically recovered from the Camden Battlefield will be laid to rest with the utmost honor and respect. No stone has been left unturned throughout the process of excavating, analyzing, and planning for the ceremony set to honor these soldiers in April – including their coffins.

Coffins, handcrafted in an eighteenth-century design is one of many paramount details made possible by volunteers and staff working on the Camden Burials project. Fortunately, both a woodworker and blacksmith living in Camden agreed to offer their talents in memorializing these soldiers.

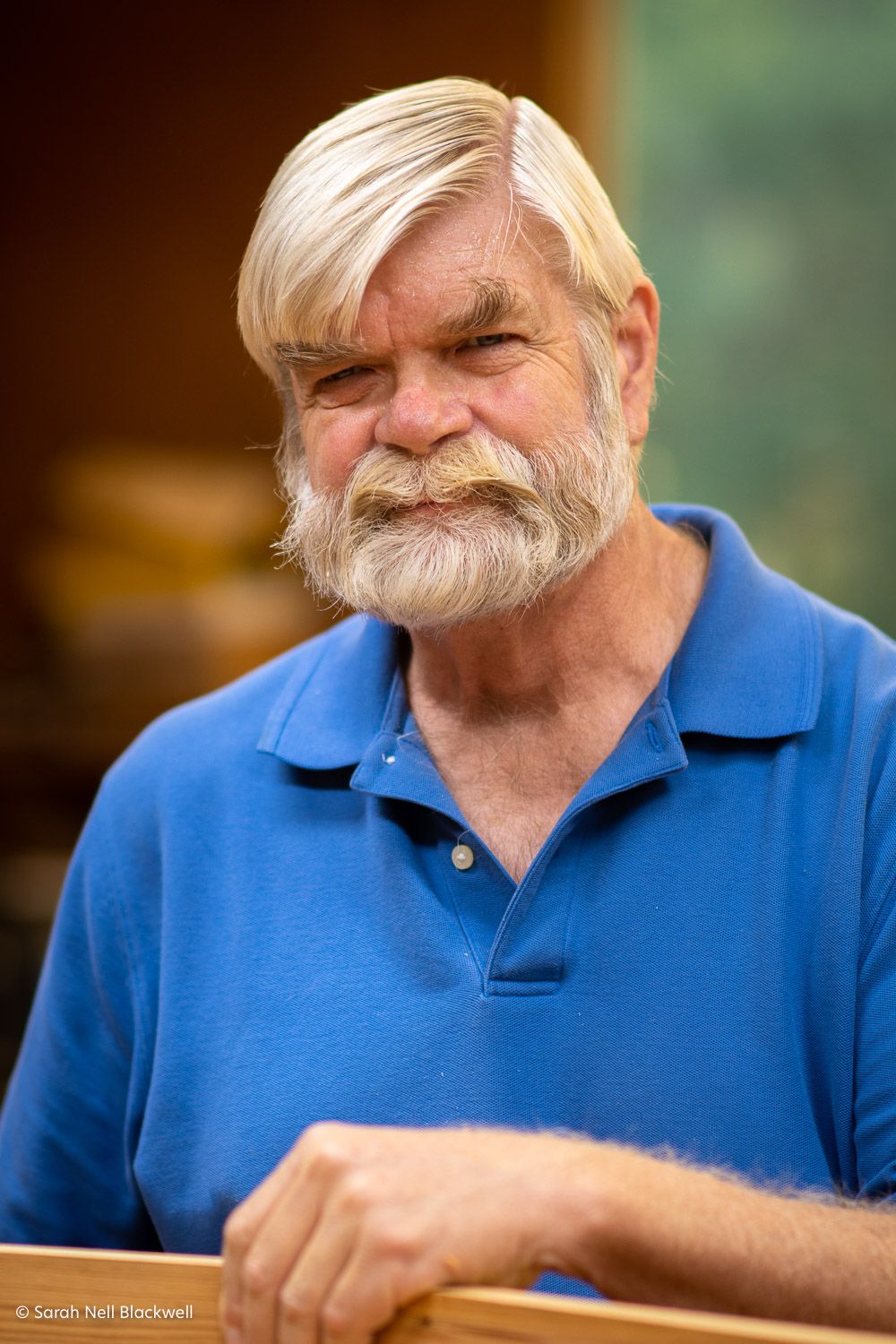

Philip Hultgren agreed to lend his woodworking expertise to build the coffins while Dr. Jack Hurley, a self-taught blacksmith, has forged each nail by hand in the on-display workshop at the Historic Camden Foundation. Both men have worked on projects with the Historic Camden Foundation previously, but this project is one that is considered not only worthwhile to them, but also an emotional process.

Hultgren was first introduced to woodworking when he was eleven. He spent many days with his grandfather, a Swedish immigrant, scouring the forest for pieces of wood to take back to the house and craft in the basement.

“My grandfather taught me important things, of sharpness and of looking, not so much following directions, but of looking at it,” Hultgren explained. “He gave me three gifts: an appreciation of what you can do with wood, the beauty of wood, and that I can make anything I see in my mind’s eye.”

Prior to pursuing woodworking as his main profession, Hultgren received a master’s degree in theology and worked as an ordained minister in two parishes. It was when he lived in St. Croix and found himself surrounded by mahogany trees knocked down during Hurricane Hugo, that his woodworking passion was reignited. Hultgren says his background in ministry has influenced his work today, by offering him a perspective to see things as larger than himself. Creating artistic pieces out of wood is a way for him to offer his gifts to others. This project has been no different.

Currently residing in Camden, it was a bit of a fluke that Hultgren began working with the Historic Camden Foundation. While recovering from an emergency eye surgery in 2019, Hultgren found himself with time on his hands to research woodworking techniques. During one of these days of recovery, he came across a water-powered sash sawmill online. Further investigation found that these sawmills were prominent in the eighteenth century with two having once existed in Camden.

Excited, Hultgren contacted Historic Camden Foundation with hopes of creating a replica for the organization to display as a new exhibit. Soon he found himself lending his skills to build other structures on the property. When approached with the proposition to build coffins for the Camden Burials project, Hultgren agreed without hesitation.

Hultgren crafted these coffins with precision and care, by ensuring the coffins are authentic to what one would have looked like in the eighteenth-century. The decision to build coffins instead of caskets is one element of authentication. Hultgren explained that caskets have four corners, while coffins have six. The coffins he has built are slightly smaller than a modern-day style, measuring out to five feet and six inches, adjusting for the fact people averaged much shorter in those days.

“In making the coffins I left them purposefully, let’s call it homespun, so they’re not perfect. The joints are all very, very close, but I did not sand them down to a super fine finish and put on coats of polyurethane to make them shine,” Hultgren describes his decisions on how he finished the coffins with only linseed oil, accurate to how it would have been in the 1700’s. “I wanted them to look like they were fashioned by someone who cared and who was a hands-on kind of person. The workmanship of risk rather than the workmanship of certainty. They’re not perfect, but they look really good, and they have that sense of this is real, this is what a family would do.”

Further adding to the authenticity is the wood Hultgren chose for the coffin. “That’s another long story”, Hultgren said with a smile in his tone. The coffins are constructed of wood from longleaf pine trees. The wood was upcycled from the Burns Hardware store in Camden. The store was first opened in 1898 by the grandfather of the current owner Jim Burns. When the shop was built, local pine was used to construct cabinets, shelves, drawers, and tables in the store. Burns reached out to Hultgren before selling the building asking him to salvage what he could of the pine, hating to think it would become scrap in future development of the store. Hultgren happily obliged and left with roughly 2500 feet of boards.

Hultgren still had much of this wood left when contacted about building the coffins. He wagers that based on the rings in the wood (about 20 rings per inch of wood) that the pines were slow growing and between two and three hundred years old when cut down. The Battle of Camden occurred in a longleaf pine forest and Hultgren believes that the pine he used in the coffins was alive and growing not far from that battlefield. A full circle moment, the pine trees that existed during the Camden battle will now serve as the vessels for the same soldiers who fought and died on those grounds, hundreds of years later. In this way, the environment and soldiers will be memorialized together in this connection of history, land, and people.

For Dr. Jack Hurley, a former history professor at the University of Memphis, this project brought a tangible connection between his background in academics and blacksmithing. He initially became interested in blacksmith work when his academic interest in folklore led him to seek physical representations of it. During his quest to learn more about folklore, Hurley spent much time in the Ozarks where he met a man running a self-sufficient homestead with a deep knowledge of the blacksmith practice. Through this individual Hurley first began learning the trade.

Hurley has been practicing blacksmithing since 1972, but it wasn’t until his retirement in 2004 that the passion took over full time. Now settled in Camden, Hurley volunteers two to three times a week at Historic Camden Foundation. He works in the blacksmith workshop, where many of the tools have been donated by him, on various projects for the foundation.

It was in this workshop that Hurley forged the nails for the coffins. The coffin boards are one inch thick, requiring each nail to be two inches long which Hurley explained is nearly four times as difficult to make as a standard 1-inch nail. The steel used for the nails is modern mill steel, the iron used in the eighteenth-century being difficult to acquire, explained Hurley, however the forging techniques used are authentic to the period. To fit with the authenticity of the period the head of each nail has four tapered corners, in contrast to a standard wire cut nail that has a rounded head. It takes about 100 blows from Hurley’s 4-pound hammer to create each nail. He averages about 30-35 nails a day, with each coffin needing 30 nails.

“Quite the physical labor for an eighty-two-year-old,” chuckled Hurley. Despite the physical demands to create these nails special to the project, it was a challenge Hurley took eagerly. He has had some assistance from Rick Thompson, another local interested in blacksmith work who helps in the shop when he can.

Between the expertise and physical labor required to materialize the vision for the coffins, it has been a project of worth and an emotional process. When asked what working on this project has meant to Hultgren, he took a breath.

After a brief period of thought he responded slightly choked up, “It’s been a lot of emotion. You think about how these remains are from people, real, honest to goodness people, who didn’t hesitate to give their lives. Here they are after they’ve fallen doing what they felt was the right thing to do- for everybody not just themselves. And to honor them by giving them a proper burial is like wow, this is really, very emotional.” After a brief pause Hultgren continued, “These guys died before their time and before their life was fully lived. They didn’t have a chance but gave that chance to so many others. But to be grateful to them for that and do what little bit I can to express that appreciation and gratitude. That’s what it means.”

These men were left on the battlefield having given their lives for a cause they all strongly believed in and now with the help of Hultgren and Hurley they will be given the honorable funeral and military burial they deserved over 200 years ago, so that they may finally rest easy.